Human Papillomavirus

Elissa Meites, MD, MPH; Julianne Gee, MPH; Elizabeth Unger, PhD, MD; and Lauri Markowitz, MD

The 14th edition of the “Pink Book” was published August 2021. Vaccine-specific recommendations may be outdated. Refer to the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices Vaccine Recommendations and Guidelines for the most updated vaccine-specific recommendations.

Printer friendly version [14 pages]

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States. Although the majority of HPV infections are asymptomatic and resolve spontaneously, persistent infections can develop into anogenital warts, precancers, and cervical, anogenital, or oropharyngeal cancers in women and men. The relationship between cervical cancer and sexual behavior was suspected for more than 100 years and was established by epidemiologic studies in the 1960s. In the early 1980s, cervical cancer cells were shown to contain HPV DNA. Epidemiologic studies demonstrating a consistent association between HPV and cervical cancer were published in the 1990s; more recently, HPV has been identified as a cause of certain other mucosal cancers. A quadrivalent vaccine to prevent infection with four types of HPV was licensed for use in the United States in 2006, a bivalent vaccine was licensed in 2009, and a 9-valent vaccine was licensed in 2014.

Human Papillomavirus (HPV)

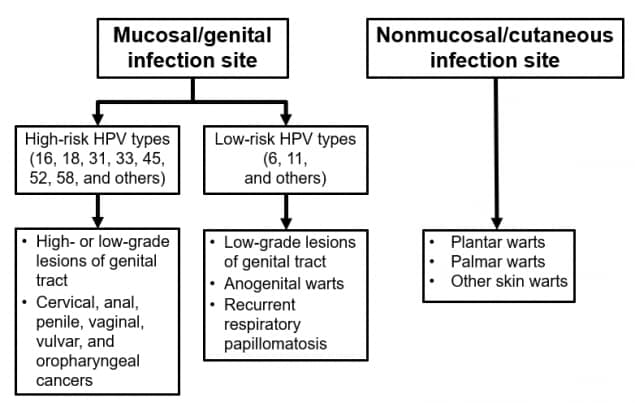

HPV consists of a family of small, double-stranded DNA viruses that infect the epithelium. More than 200 distinct types have been identified; they are differentiated by their genomic sequence. Most HPV types infect the cutaneous epithelium and can cause common skin warts. About 40 types infect the mucosal epithelium; these are categorized according to their epidemiologic association with cervical cancer.

Infection with low-risk or nononcogenic types, such as types 6 or 11, can cause benign or low-grade cervical cell abnormalities, anogenital warts, and respiratory tract papillomas. More than 90% of cases of anogenital warts are caused by low-risk HPV types 6 or 11.

High-risk or oncogenic HPV types act as carcinogens in the development of cervical cancer and other anogenital cancers. High-risk types (including types 16, 18, and others) can cause low-grade cervical cell abnormalities, high-grade cervical cell abnormalities that are precursors to cancer, and anogenital cancers. High-risk HPV types are detected in 99% of cervical precancers. Type 16 is the cause of approximately 50% of cervical cancers worldwide, and types 16 and 18 together account for about 66% of cervical cancers. An additional five high-risk types, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58, are responsible for another 15% of cervical cancers and 11% of all HPV-associated cancers. Infection with a high-risk HPV type is considered necessary for the development of cervical cancer but, by itself, is not sufficient to cause cancer. The vast majority of women with HPV infection, even those with high-risk HPV types, do not develop cancer.

In addition to cervical cancer, high-risk HPV infection is associated with less common anogenital cancers, such as cancer of the vulva, vagina, penis, and anus. These HPV types can also cause oropharyngeal cancers.

Pathogenesis

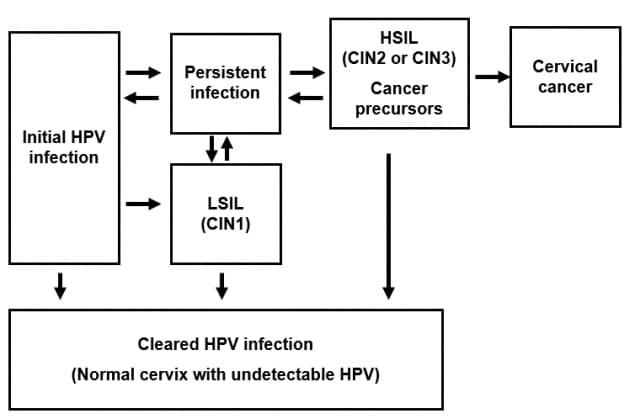

HPV infection occurs at the basal epithelium. Although incidence of infection is high, most infections resolve spontaneously within a year or two. A small proportion of infected persons become persistently infected; persistent infection is the most important risk factor for the development of cervical cancer.

In women, squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL) of the cervix can be detected through screening. Low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL) often regress. High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) are considered cancer precursors. Previously, these types of cervical lesions were called cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). If left undetected and untreated, such cancer precursors can progress to cervical cancer years or decades later.

The pathogenesis of other types of HPV-related cancers may follow a similar course, although less is known about their respective precursor lesions: anal HSIL has been identified as a precursor to anal cancer, vulvar HSIL has been identified as a precursor to vulvar cancer, and vaginal HSIL has been identified as a precursor to vaginal cancer.

Infection with one type of HPV does not prevent infection with another type. Of persons infected with HPV that infects the mucosal epithelium, 5% to 30% are infected with multiple types of the virus.

HPV Clinical Features

- Most HPV infections are asymptomatic and result in no clinical disease

- Clinical manifestations of HPV infection include:

- Anogenital warts

- Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis

- Cervical cancer precursors (HSIL)

- Cancer (cervical, anal, vaginal, vulvar, penile, and oropharyngeal cancer)

Clinical Features

Most HPV infections are asymptomatic and result in no clinical disease. Clinical manifestations of HPV infection include anogenital warts, recurrent respiratory papillomatosis, cancer precursors or cancers, including cervical, anal, vaginal, vulvar, penile, or oropharyngeal cancers.

Medical Management

No specific treatment is required or recommended for asymptomatic HPV infection. Medical management is recommended for treatment of specific clinical manifestations of HPV-related disease (e.g., anogenital warts, precancerous lesions, or cancers).

Laboratory Testing

HPV is not cultured by conventional methods. Infection is identified by detection of HPV DNA from clinical specimens. Assays for HPV detection differ considerably in their sensitivity and type specificity, and detection is also affected by the anatomic region sampled, as well as the method of specimen collection.

Several HPV tests have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and detect up to 14 high-risk types (HPV 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68). Test results are reported as positive when the presence of any combination of these HPV types is detected; certain tests specifically identify HPV types 16 and/or 18. These tests are approved for use in women as part of cervical cancer screening either as primary screen, co-test with cytology, or management of abnormal cervical cytology results on a Papanicolaou (Pap) test. HPV tests are neither clinically indicated nor approved for use in men.

Epidemiologic and basic research studies of HPV generally use nucleic acid amplification methods that generate type-specific results. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays used most commonly in epidemiologic studies target genetically conserved regions in the L1 gene.

The most frequently used HPV serologic assays are virus-like-particle-(VLP)-based enzyme immunoassays. However, laboratory reagents used for these assays are not standardized and there are no standards for setting a threshold for a positive result. Serology results are not used clinically.

HPV Epidemiology

- Reservoir

- Human

- Transmission

- Direct contact, usually sexual

- Temporal pattern

- None

- Communicability

- Presumed to be high

- Risk factors

- Sexual behavior, including higher number of lifetime and recent sex partners

Epidemiology

Occurrence

HPV infection is extremely common throughout the world. Most sexually active adults will have an HPV infection at some point during their lives, although they may be unaware of their infection.

Reservoir

Humans are the only natural reservoir for HPV. Other viruses in the papillomavirus family affect other species.

Transmission

HPV is transmitted through intimate, skin-to-skin contact with an infected person. Transmission is most common during vaginal, penile, anal, or oral sex.

Studies of newly acquired HPV infection demonstrate that infection typically occurs soon after first sexual activity. In a prospective study of college women, the cumulative incidence of infection was 40% by 24 months after first sexual intercourse, and 10% of infections were caused by HPV 16.

Autoinoculation from one body site to another can occur.

Very rarely, vertical transmission of HPV from an infected mother to her infant can result in a condition called juvenile-onset recurrent respiratory papillomatosis.

Temporal Pattern

There is no known seasonal variation in HPV infection.

Communicability

HPV is presumed to be communicable during both acute and persistent infections. Communicability can be presumed high because of the large number of new infections estimated to occur each year.

Risk Factors

Risk factors for HPV infection are primarily related to sexual behavior, including higher numbers of lifetime and recent sex partners. Results of epidemiologic studies are less consistent for other risk factors, including younger age at sexual initiation, higher number of pregnancies, genetic factors, smoking, and lack of circumcision of the male partner.

HPV Secular Trends in the United States

- Genital HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the U.S.

- Common among adolescents and young adults

- Before vaccine introduction

- Estimated 79 million infected

- 14 million new infections/year

- Within 10 years following vaccine introduction, prevalence of HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 has decreased:

- 86% among females age 14 through 19 years

- 71% among females age 20 through 24 years

Secular Trends in the United States

Genital HPV infection is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States and worldwide.

Based on data from 2003-2006 (before vaccine introduction), an estimated 79 million persons were infected in the United States. Approximately 14 million new HPV infections occurred annually, with nearly half occurring in persons age 15 through 24 years. During 2013–2014, genital prevalence of any of 37 HPV types assayed was 45.2% and prevalence of high-risk HPV types was 25.1% among U.S. men age 18 through 59 years. Also during this period, genital prevalence of any of 37 HPV types assayed was 39.9% and prevalence of high-risk HPV types was 20.4% among U.S. women in the same age range. Within a decade following the U.S. introduction of quadrivalent HPV vaccine in 2006, prevalence of HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 decreased 86% among females age 14 through 19 years and decreased 71% among females age 20 through 24 years.

The National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program and CDC’s National Program of Cancer Registries provide data on the number of HPV cancers in the United States. On average, 43,999 HPV-associated cancers are reported annually, including 24,886 in females and 19,113 in males. By gender, the most common cancers attributed to HPV are an estimated 10,900 cervical cancers in women and 11,300 oropharyngeal cancers in men.

In addition to 91% of cervical cancer, HPV is responsible for about 91% of anal cancers, 69% of vulvar cancers, 75% of vaginal cancers, 63% of penile cancers, and 70% of oropharyngeal cancers.

On the basis of health claims data in the United States, the incidence of anogenital warts in 2004 (before vaccine introduction) was 1.2 per 1,000 females and 1.1 per 1,000 males. During 2003–2010, reductions in anogenital wart prevalence were observed among U.S. females age 15 through 24 years, the group most likely to be affected by introduction of HPV vaccine. By 2014, decreasing prevalence of anogenital warts was also identified in young men.

From 2008–2015, both CIN grade 2 or worse (CIN2+) rates and cervical cancer screening declined among women age 18 through 24 years. Significant decreases in CIN2+ rates among screened women in this age group were consistent with population-level impact of HPV vaccination.

Among adolescents age 13 through 17 years in 2019, 71.5% had received at least 1 dose of HPV vaccine, and 54.2% were up-to-date with HPV vaccination (including adolescents who received an HPV vaccine series of 2 doses initiated before age 15 years, or else 3 doses, at the recommended intervals). Among females, 73.2% had received at least 1 dose of HPV vaccine and 56.8% were up-to-date with HPV vaccination. Among males, 69.8% had received at least 1 dose of HPV vaccine and 51.8% were up-to-date with HPV vaccination. Each of these coverage estimates represents a statistically significant increase in HPV vaccination coverage from 2018.

Cervical Cancer Screening

- Annual cervical cancer screening not recommended for average-risk individuals

- For ages 21 through 29 years, screen with cytology testing every 3 years

- For ages 30 through 65 years, screen with choice of cytology test every 3 years, an HPV test alone every 5 years, or cytology test plus HPV test every 5 years

- USPSTF and ACOG have similar screening recommendations; ACS recommends that screening start at age 25 years for average-risk persons.

- HPV vaccination does not eliminate the need for cervical cancer screening

Prevention

Vaccination prevents HPV infection, benefitting both the vaccinated person and their future sex partners by preventing spread of HPV. HPV transmission can be reduced, but not eliminated, with the consistent and correct use of physical barriers such as condoms.

Cervical Cancer Screening

Most cases of and deaths from cervical cancer can be prevented through screening and treatment. The Pap test detects precancerous changes in cervical cells collected by a health care provider and placed on a slide (a conventional Pap) or in liquid media (liquid-based cytology). Clinical tests for HPV can be used as a primary screen either alone or in combination with cytology (co-test) or as triage after an equivocal cytology result.

Recommendations for cervical cancer screening in the United States are based on systematic evidence reviews by major medical and other organizations including the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), American Cancer Society (ACS), and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Annual cervical cancer screening is not recommended for average-risk individuals. Instead, cytology testing is recommended every 3 years from age 21 through 29 years. Between age 30 and 65 years, a choice of a cytology test every 3 years, an HPV test alone every 5 years, or cytology test plus an HPV test (co-test) every 5 years is recommended. Co-testing can be done by either collecting one sample for the cytology test and another for the HPV test or by using the remaining liquid cytology material for the HPV test. Cervical screening programs should screen those who have received HPV vaccination in the same manner as those who are unvaccinated. Screening is not recommended before age 21 years in those at average risk. For those age 30 to 65 years, cytology alone or primary HPV testing are preferred by USPSTF, but co-testing can be used as an alternative approach. USPSTF and ACOG have similar screening recommendations. ACS recommends that screening start at age 25 years for average-risk persons.

HPV Vaccines

- 9vHPV (Gardasil 9) is licensed and currently distributed in the U.S.

- Prevents HPV types 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, 58

- 4vHPV and 2vHPV are licensed but not currently distributed in the U.S.

- 4vHPV prevents HPV types 6, 11, 16, 18

- 2vHPV prevents HPV types 16, 18

HPV vaccination does not eliminate the need for continued cervical cancer screening, since up to 30% of cervical cancers are caused by HPV types not prevented by the quadrivalent or bivalent vaccines, and 15% of cervical cancers are caused by HPV types not prevented by the 9-valent vaccine.

Human Papillomavirus Vaccines

A 9-valent recombinant protein subunit HPV vaccine (9vHPV, Gardasil 9) is licensed for use and is currently distributed in the United States. Two additional HPV vaccines remain licensed in the United States but are not currently distributed: a quadrivalent HPV vaccine (4vHPV, Gardasil), and a bivalent HPV vaccine (2vHPV, Cervarix). All of the vaccines prevent infection with high-risk HPV types 16 and 18, types that cause most cervical and other cancers attributable to HPV; 9vHPV vaccine also prevents infection with five additional high-risk types. In addition, 4vHPV and 9vHPV vaccines prevent infections with HPV types 6 and 11, types that cause anogenital warts.

HPV Vaccine Characteristics

- HPV L1 major capsid protein of the virus is antigen used for immunization

- L1 protein produced using recombinant technology

- L1 proteins self-assemble into virus-like particles (VLP)

- VLPs are noninfectious and nononcogenic

- Administer by intramuscular injection

- 9vHPV contains yeast protein

- 9vHPV contains aluminum adjuvant

Characteristics

The antigen for HPV vaccines is the L1 major capsid protein of HPV, produced by using recombinant DNA technology. L1 proteins self-assemble into noninfectious, nononcogenic units called virus-like particles (VLPs). The L1 proteins are produced by fermentation using Saccharomyces cerevisiae yeast; 9vHPV vaccine contains yeast protein. 9vHPV vaccine contains VLPs for nine HPV types: two types that cause anogenital warts (HPV types 6 and 11) and seven types that can cause cancers (HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58). 9vHPV vaccine is administered by intramuscular injection. Each dose of 9vHPV vaccine contains aluminum as an adjuvant. It contains no antibiotic or preservative.

Vaccination Schedule and Use

HPV Vaccine Recommendations

- Routine vaccination recommended for females and males at age 11 or 12 years (minimum age 9 years)

- Catch-up vaccination recommended for all persons not adequately vaccinated through age 26 years

- Catch-up vaccination not recommended for all adults over age 26 years

- Shared clinical decision-making is recommended for some adults age 27 through 45 years

- Not licensed for adults over age 45

HPV vaccination is recommended for females and males at age 11 or 12 years for prevention of HPV infections and HPV-associated diseases, including certain cancers. The vaccination series can be started at age 9 years. Catch-up HPV vaccination is recommended for all persons through age 26 years who are not adequately vaccinated. Catch-up HPV vaccination is not recommended for all adults older than age 26 years, since the public health benefit of vaccination in this age range is minimal. HPV vaccines are not licensed for use in persons older than age 45 years.

HPV vaccines are administered as a 2- or 3-dose series, depending on age at initiation and medical conditions.

A 2-dose series is recommended for persons who receive the first valid dose before their 15th birthday (except for persons with certain immunocompromising conditions). The second and final dose should be administered 6 through 12 months after the first dose (0, 6-12 month schedule). If dose 2 is administered at least 5 months after the first dose, it can be counted as valid. If dose 2 is administered at a shorter interval, an additional dose should be administered at least 12 weeks after dose 2 and at least 6 to 12 months after dose 1.

HPV Vaccination Schedule

- 2-dose series

- For immunocompetent persons who receive first valid dose before 15th birthday

- 0, 6-12 month schedule

- Minimum interval of 5 months

- 3-dose series

- For persons who receive first valid dose on or after 15th birthday

- For persons with primary or secondary immunocompromising conditions

- 0, 1-2, 6 month schedule

- Series does not need to be restarted if the schedule is interrupted

- Prevaccination assessments not recommended

- No therapeutic effect on existing HPV infection, anogenital warts, or HPV-related lesions

A 3-dose series is recommended for persons who receive the first valid dose on or after their 15th birthday, and for persons with primary or secondary immunocompromising conditions that might reduce cell-mediated or humoral immunity, such as B lymphocyte antibody deficiencies, T lymphocyte complete or partial defects, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, malignant neoplasm, transplantation, autoimmune disease, or immunosuppressive therapy, in whom immune response to vaccination may be attenuated. In a 3-dose schedule, dose 2 should be administered 1 through 2 months after dose 1, and dose 3 should be administered 6 months after dose 1 (0, 1–2, 6 month schedule).

There is no maximum interval between doses. If the HPV vaccination schedule is interrupted, the vaccine series does not need to be restarted. For persons who already received 1 dose of HPV vaccine before their 15th birthday, and now are age 15 years or older, the 2-dose series is considered adequate. If the series was interrupted after dose 1, dose 2 should be administered as soon as possible.

Routine HPV vaccination is recommended beginning at 9 years of age for children with any history of sexual abuse or assault.

Ideally, vaccine should be administered before any exposure to HPV through sexual contact. However, persons in the routine and catch-up age ranges (through age 26 years) should be vaccinated, even if they might have been exposed to HPV in the past.

Vaccination will provide less benefit to sexually active persons who have been already infected with one or more HPV vaccine types. However, HPV vaccination can provide protection against HPV vaccine types not already acquired. Recipients may be advised that prophylactic vaccine is not expected to have a therapeutic effect on existing HPV infection, anogenital warts, or HPV-related lesions.

HPV vaccine should be administered at the same visit as other age-appropriate vaccines, such as Tdap and quadrivalent meningococcal conjugate (MenACWY) vaccines. Administering all indicated vaccines at a single visit increases the likelihood that patients will receive each of the vaccines on schedule. Each vaccine should be administered using a separate syringe at a different anatomic site.

Catch-up vaccination is recommended through age 26 years. Above this age, shared clinical decision-making regarding HPV vaccination is recommended for some adults age 27 through 45 years who are not adequately vaccinated. HPV vaccination does not need to be discussed with most adults over age 26 years; clinicians can consider discussing HPV vaccination with persons who are most likely to benefit.

Considerations for shared clinical decision-making regarding HPV vaccination of adults age 27 through 45 years include:

- HPV is a very common sexually transmitted infection. Most HPV infections are transient and asymptomatic and cause no clinical problems.

- Although new HPV infections are most commonly acquired in adolescence and young adulthood, some adults are at risk for acquiring new HPV infections. At any age, having a new sex partner is a risk factor for acquiring a new HPV infection.

- Persons who are in a long-term, mutually monogamous sexual partnership are not likely to acquire a new HPV infection.

- Most sexually active adults have been exposed to some HPV types, although not necessarily to all of the HPV types targeted by vaccination.

- No clinical antibody test can determine whether a person is already immune or still susceptible to any given HPV type.

- HPV vaccine efficacy is high among persons who have not been exposed to vaccine-type HPV before vaccination.

- Vaccine effectiveness might be low among persons with risk factors for HPV infection or disease (e.g., adults with multiple lifetime sex partners and likely previous infection with vaccine-type HPV), as well as among persons with certain immunocompromising conditions.

- HPV vaccines are prophylactic (i.e., they prevent new HPV infections). They do not prevent progression of HPV infection to disease, decrease time to clearance of HPV infection, or treat HPV-related disease.

Prevaccination assessments (e.g., HPV testing of any kind, cervical cancer screening or Pap testing, pregnancy testing, or “virginity testing”) are not required. No prevaccination testing (e.g., Pap or HPV testing) is recommended to establish the appropriateness of HPV vaccination.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) has not preferentially recommended any of the licensed HPV vaccines. There is no ACIP recommendation for additional vaccination with 9vHPV for persons who have completed a series with one of the other recommended HPV vaccines.

Vaccine recipients should always be seated during vaccine administration. Because syncope has sometimes been reported in association with HPV vaccination, clinicians should consider observing recipients for 15 minutes after vaccination.

HPV Vaccine Efficacy

- High vaccine efficacy

- More than 98% of recipients develop an antibody response to covered HPV types within one month after completing the series

- No evidence of efficacy against disease caused by vaccine types with which participants were infected at the time of vaccination

- Prior infection with one HPV type did not diminish efficacy of the vaccine against other vaccine HPV types

Immunogenicity and Vaccine Efficacy

HPV vaccine is highly immunogenic. More than 98% of recipients develop an antibody response to each covered HPV type within one month after completing the vaccine series. However, there is no known serologic correlate of protection and the minimum antibody titer needed for protection has not been determined. The high efficacy found in the clinical trials has precluded identification of this threshold. Further follow-up of vaccinated cohorts might allow determination of serologic correlates of protection in the future.

All licensed HPV vaccines have high efficacy for prevention of HPV vaccine-type-related persistent infection, CIN2+, and adenocarcinoma in-situ (AIS). Prelicensure, clinical efficacy for 4vHPV was assessed in phase III clinical trials. To date, ongoing monitoring has demonstrated that vaccine effectiveness remains above 90%, with no waning of immunity through at least 10 to 12 years after immunization.

Although high efficacy was demonstrated among persons without evidence of prior infection with HPV vaccine types in clinical trials, there was no evidence of efficacy against disease caused by vaccine types with which participants were already infected at the time of vaccination (i.e., the vaccines had no therapeutic effect on existing infection or disease). Participants infected with one or more HPV vaccine types prior to vaccination were protected against disease caused by the other vaccine types. Prior infection with one HPV type did not diminish vaccine efficacy against other HPV vaccine types.

HPV Vaccine Contraindications and Precautions

- Contraindication

- Severe allergic reaction to a vaccine component or following a prior dose

- History of immediate hypersensitivity to yeast (4vHPV and 9vHPV only)

- Anaphylactic allergy to latex (2vHPV only)

- Precaution

- Moderate or severe acute illnesses (defer until symptoms improve)

Contraindications and Precautions to Vaccination

As with other vaccines, a history of a severe allergic reaction (anaphylaxis) to a vaccine component or following a prior dose is a contraindication to further doses. Moderate or severe acute illness (with or without fever) in a patient is considered a precaution to vaccination, although persons with minor illness may be vaccinated.

Both 4vHPV and 9vHPV are produced using Saccharomyces cerevisiae (baker’s yeast) and thus are contraindicated for persons with a history of immediate hypersensitivity to yeast. 2vHPV should not be used in persons with an anaphylactic allergy to latex as the pre-filled syringes might contain latex in the tip cap.

Vaccination during Pregnancy

HPV Vaccination During Pregnancy

- Initiation of the vaccine series should be delayed until after completion of pregnancy

- If a woman is found to be pregnant after initiating the vaccination series, remaining dose(s) should be delayed until after the pregnancy

- If a vaccine dose has been administered during pregnancy, there is no indication for intervention

- Women vaccinated during pregnancy should be reported to the manufacturer

- Pregnancy testing is not needed before vaccination

HPV vaccines are not recommended for use during pregnancy. If a person is found to be pregnant after starting the vaccine series, the remainder of the series should be delayed until after pregnancy. If a vaccine dose has been administered during pregnancy, no intervention is needed. Pregnancy testing is not needed before vaccination.

A pregnancy registry has been established by the manufacturer of 9vHPV. Women exposed to this vaccine around the time of conception or during pregnancy are encouraged to be registered by calling 1-800-986-8999 (merckpregnancyregistries.com/gardasil9.html).

Persons who are lactating or breastfeeding can receive HPV vaccine.

Vaccine Safety

HPV vaccine is generally well-tolerated. Safety has been well-established from prelicensure trials and postlicensure monitoring and evaluation.

HPV Vaccine Safety

- HPV vaccine is generally well-tolerated

- Local reactions (pain, redness, swelling)

- 20%-90%

- Fever (100°F)

- 10%-13% (similar to reports in placebo recipients)

- Anaphylaxis is rare, but can occur

- No other serious adverse reactions associated with any HPV vaccine

The most common adverse reactions reported during clinical trials of HPV vaccines were local reactions at the site of injection. In prelicensure clinical trials, local reactions, such as pain, redness, or swelling were reported by 20% to 90% of recipients. A temperature of 100°F during the 15 days after vaccination was reported by 10% to 13% of HPV vaccine recipients. A similar proportion of placebo recipients reported an elevated temperature. Local reactions generally increased in frequency with increasing doses. However, reports of fever did not increase significantly with increasing doses. Although rare, anaphylaxis can occur. No other serious adverse events have been significantly associated with any HPV vaccine, based on monitoring by CDC and FDA.

A variety of systemic adverse events following vaccination were reported by vaccine recipients, including nausea, dizziness, myalgia, and malaise. However, these symptoms occurred with similar frequency among vaccine and placebo recipients.

Postlicensure monitoring of reports from the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) did not identify any unexpected adverse event, was consistent with data from prelicensure clinical trials, and supports the safety data for 9vHPV. The Vaccine Safety Datalink did not identify any new safety concerns after monitoring around 839,000 doses of 9vHPV administered during 2015–2017.

Because syncope has sometimes been reported, vaccine recipients should always be seated during vaccine administration. Clinicians should consider observing recipients for 15 minutes after vaccination.

Vaccine Storage and Handling

HPV vaccines should be maintained at refrigerator temperature between 2°C and 8°C (36°F and 46°F). Manufacturer package inserts contain additional information. For complete information on best practices and recommendations for vaccine storage and handling, please refer to CDC’s Vaccine Storage and Handling Toolkit [3 MB, 65 pages].

Surveillance and Reporting of HPV Infection

HPV infection is not a nationally notifiable condition. For information on guidance for state and local health department staff who are involved in surveillance activities for vaccine-preventable diseases, please consult the Manual for the Surveillance of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases.

Acknowledgements

The editors would like to acknowledge Valerie Morelli, Ginger Redmon, and Mona Saraiya for their contributions to this chapter.

Selected References

CDC. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR 2019;68(32):698–702.

CDC. Human papillomavirus vaccination: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR 2014;63(RR-05):1–30.

CDC. Use of a 2-dose schedule for human papillomavirus vaccination—updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR 2016;65(49):1405–8.

CDC. Use of 9-valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: updated HPV vaccination recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR 2015;64(11):300–4.

Curry S, Krist A, Owens D, et al.; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: US Prevention Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 2018;320(7):674–86.

Donahue J, Kieke B, Lewis E, et al. Near real-time surveillance to assess the safety of the 9-valent human papillomavirus vaccine. Pediatrics 2019 Dec:144(6):e20191808.

Drolet M, Bénard É, Pérez N, et al; Vaccination Impact Study Group. Population-level impact and herd effects following the introduction of human papillomavirus vaccination programmes: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2019;394(10197):497–509.

Fontham E, Wolf A, Church T, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at risk: 2020 guidelines update from the American Cancer Society. Cancer J Clin 2020;1–26.

Food and Drug Administration. Prescribing information (package insert). Gardasil 9 (human papillomavirus 9-valent vaccine, recombinant). Silver Spring, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration; 2020. Accessed September 10, 2020.

FUTURE II Study Group. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent high-grade cervical lesions. N Engl J Med 2007;356(19):1915–27.

Gargano J, Park I, Griffin M, et al. Trends in high-grade cervical lesions and cervical cancer screening in 5 states, 2008–2015. Clin Infect Dis 2019;68(8):1282–91.

Garland S, Hernandez-Avila M, Wheeler C, et al; Females United to Unilaterally Reduce Endo/Ectocervical Disease (FUTURE) I Investigators. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent anogenital diseases. N Engl J Med 2007;356(19):1928–43.

Giuliano A, Palefsky J, Goldstone S, et al. Efficacy of quadrivalent HPV vaccine against HPV infection and disease in males. N Engl J Med 2011;364(5):401–11.

Iverson O, Miranda M, Ulied A, et al. Immunogenicity of the 9-valent HPV vaccine using 2-dose regimens in girls and boys vs a 3-dose regimen in women. JAMA 2016;316(22):2411–21.

Joura E, Giuliano A, Iversen O, et al. Broad Spectrum HPV Vaccine Study. A 9-valent HPV vaccine against infection and intraepithelial neoplasia in women. N Engl J Med 2015;372(8):711–23.

Kjaer S, Nygárd M, Dillner J, et al. A 12-year follow-up on the long-term effectiveness of the quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine in 4 Nordic countries. Clin Infect Dis 2018;66(3):339–45.

McClung N, Lewis R, Gargano J, et al. Declines in vaccine-type human papillomavirus prevalence in females across racial/ethnic groups: data from a national survey. J Adolesc Health 2019;65(6):715–22.

Moreira E Jr., Block S, Ferris D, et al. Safety profile of the 9-valent HPV vaccine: a combined analysis of 7 phase III clinical trials. Pediatrics 2016;138(2):e20154387.

Muñoz N, Bosch F, de Sanjosé S, et al; International Agency for Research on Cancer Multicenter Cervical Cancer Study Group. Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. N Engl J Med 2003;348(6):518–27.

Owusu-Edusei K Jr., Chesson H, Gift T, et al. The estimated direct medical cost of selected sexually transmitted infections in the United States, 2008. Sex Transm Dis 2013;40(3):197–201.

Palefsky J, Giuliano A, Goldstone S, et al. HPV vaccine against anal HPV infection and anal intraepithelial neoplasia. N Engl J Med 2011;365(17):1576–85.

Phillips A, Patel C, Pillsbury A, et al. Safety of human papillomavirus vaccines: an updated review. Drug Saf 2018;41(4):329–46.

Satterwhite C, Torrone E, Meites E, et al. Sexually transmitted infections among US women and men: prevalence and incidence estimates, 2008. Sex Transm Dis 2013;40(3):187–93.

Senkomago V, Henley S, Thomas C, et al. Human papillomavirus-attributable cancers—United States, 2012–2016. MMWR 2019;68(33):724–8.

Shimabukuro T, Su J, Marques P, et al. Safety of the 9-valent human papillomavirus vaccine. Pediatrics. 2019;144(6):e20191791.

Winer R, Lee S, Hughes J, et al. Genital human papillomavirus infection incidence and risk factors in a cohort of female university students. Am J Epidemiol 2003;157(3):218–26.